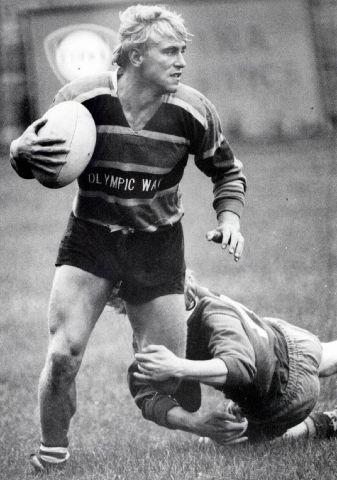

Once tipped as one of the finest wingers to be seen in chocolate, blue and gold, Jimmy Dalton’s rugby career was halted in his prime.

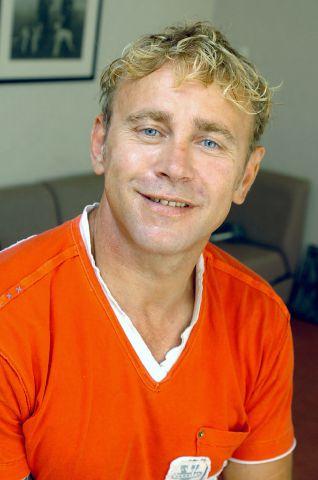

In 2006, the former Haven winger, who died this week, spoke to our sister paper The Whitehaven News about his career and the illness which put paid to his international hopes.

Dalton said: “One moment I was on top of the world in the prime of my life, then the whole world around me collapsed. I didn’t know what was happening to me and neither did the doctors. It was absolutely horrible.”

The determination that Jimmy Dalton showed on the rugby field for Whitehaven and Great Britain was matched by his sheer courage fighting a serious illness.

At the height of his powers, with a call up to full Great Britain honours imminent, the Hensingham lad was struck down with Castleman’s syndrome.

He said: “For years, my illness was wrongly diagnosed. It was thought at first to be cancer of the lymphoma — they operated on me, took a piece of spleen, it came back negative. Then they did more scans, and bone marrow tests. I’ve been in all the top hospitals all over the country seeing these top medical professors and no-one could say what it really was until now.

“It’s like having lots of tiny benign tumours inside your body reacting to the white cells, so I was being attacked by my own immune system which thinks I am a foreign body. I was only 23 or 24 when the illness started. My world was crashing around me.”

Already a BARLA Young Lion in New Zealand, with Gary Schofield as his centre, Jimmy Dalton went on to be capped for Great Britain under-21s and was expected to be called up to the full international team at any time to face the mighty Kangaroos Invincibles in 1986, such was his breathtaking form for Whitehaven.

In his youth at Hensingham, Dalton – fast, powerful and hungry for tries – was nicknamed the Exocet.

And at Whitehaven, the crowd loved to chant “Give the ball to Jimmy” because every time he got the ball on the right wing there was an expectation that something would happen. He was being tipped to become the finest specialist wingman to play for the club. Then came the first setback – a dislocated shoulder against Sheffield.

But within 24 hours of the injury, Maurice Bamford, the British coach, sent him the message: “Listen kid, don’t worry about it. Get fit again, play like hell for your club and I will do the rest.”

“Unfortunately, the injury took its toll, the shoulder came out again and it was the start of the downfall,” said Jimmy.

“Then one day, while I was working at Sellafield, I thought I had flu. The doctor sent off blood tests and I just got steadily worse. I was in hospital for five months [until February 1988] and put on steroids, which was the only treatment available.

“I didn’t know what was going on and neither really did the doctors at that time... unbelievable. After that I never wore a rugby jersey again. I was devastated.”

Arnold “Boxer” Walker, all-time Cumberland great scrum half, remembered Jimmy well. He said at the time: “He was a crowd puller — every time he got the ball the fans erupted.

“If you have a big heart you are halfway to becoming one hell of a rugby player. Jimmy’s heart was double his size. He was such a talented player that nobody knows what his potential would have been. Chocolate, blue and gold ran through his veins. What happened was a tragedy.”

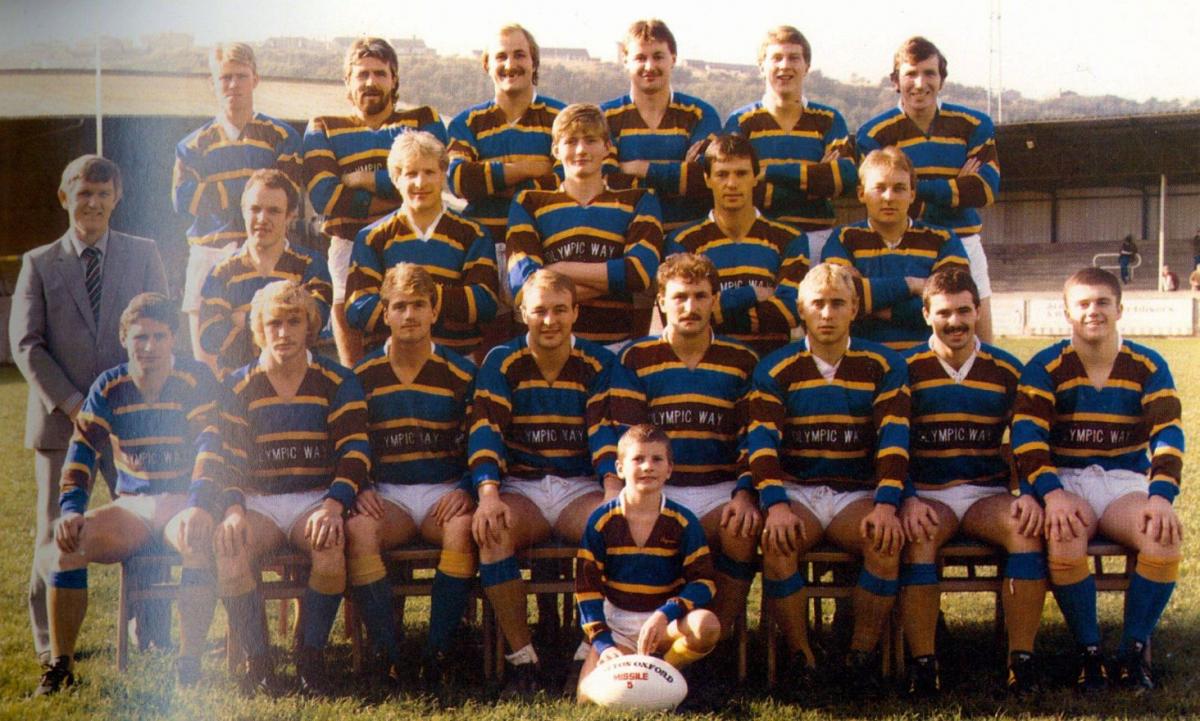

Whitehaven had its best crop of youngsters for many a year at the time, with Vince Gribbin, Mark Beckwith and Dalton all playing in the Great Britain under-21 threequarter line.

He remembered: “It was unique for the club. We had an exciting young team, with the likes of Dave Lightfoot, who could easily have played for the full international team, Stephen Burney – another Egremont lad – and Milton Huddart.

“I think we got promoted to the old First Division too soon. We were all young kids moving into a higher class of rugby and there were a lot of expectations on our shoulders.

“Milton Huddart was excellent. We had this move on the blind side so that every time we got a penalty maybe 20 yards from the line, Milton would pretend to be injured and so when the opposition took their eyes off him he’d would suddenly come through on the bang, take the ball and put me in for another try.

“Becky [Beckwith] was my centre partner. We played well together on the right, but I also scored a lot on the left because if I wasn’t getting any ball I used to roam round the field, which wasn’t very nice for Tony Solarie, a real flyer, on the left wing. I was coming in between him and the centres and scoring tries. Poor Tony was saying ‘those should have been mine’.”

But at the end of the day the flier admitted he just wanted to make his family proud.

He added: “I come from a big family, five sisters and two brothers. Really, we didn’t have anything. I just wanted to do well for them and make my mam and dad proud to come and watch me play.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here