IF YOU were a well-to-do family living in Whitehaven in the late 18th early 19th century, chances are you had some involvement in the slave trade. Many ships had multiple owners and investors so that financial risk was shared, with quite a number of local people having a stake in the opportunity to make money.

Many prospered on the back of the slave trade – not least the bankers who put up the money for such sea-going and far-flung ventures, backed of course by watertight guarantees.

Some old papers show that when plantation heir John Simpson’s Jamaican estates were overwhelmed by debt in the 1820s, it was the Hartleys, bankers of Whitehaven, who moved in to claim their dues. Simpson owed almost £93,000 (over £10 million today) to three parties, including the Hartleys and Liverpool merchant Adam Cliff. Between them Cliff and Hartleys’ Bank were owed almost £55,000.

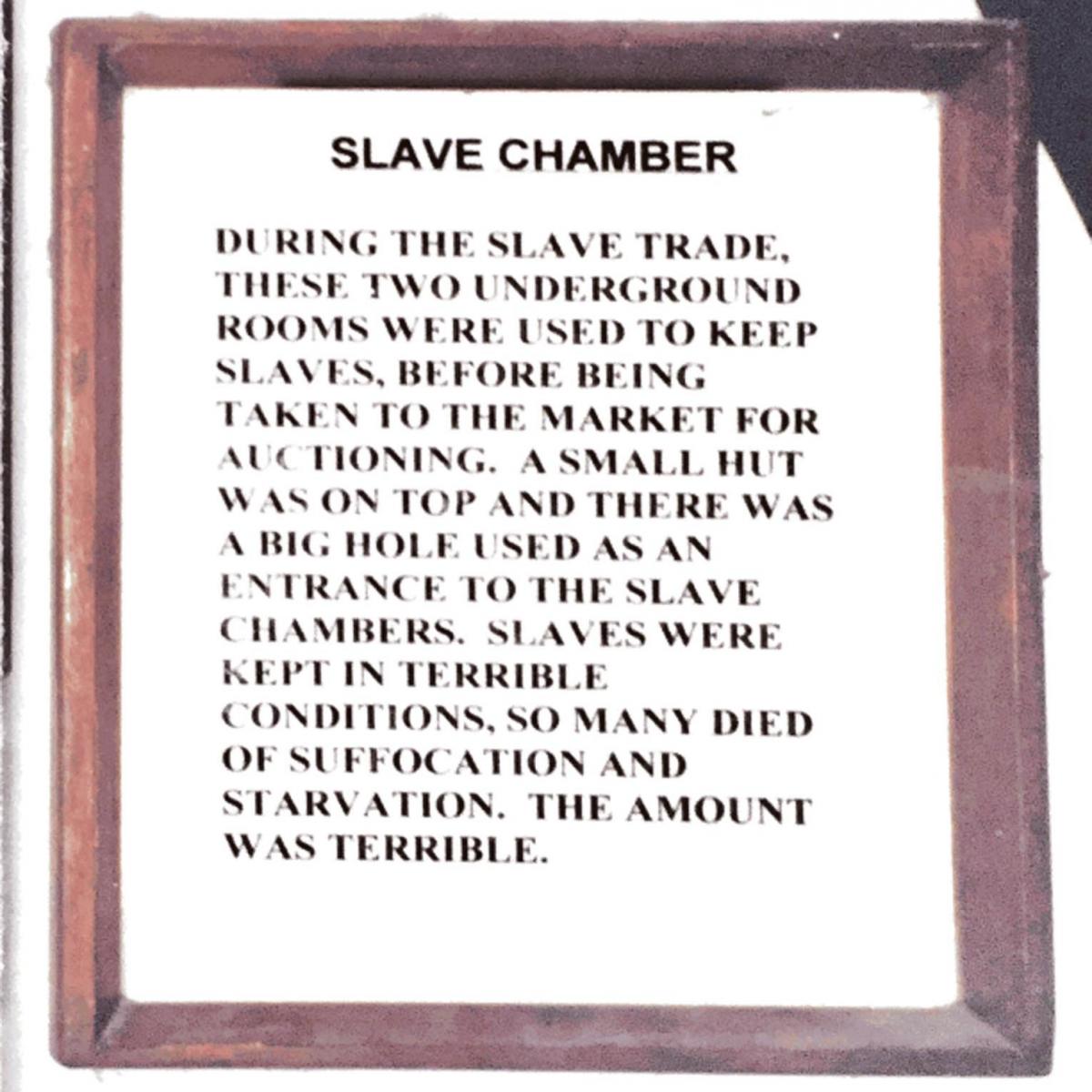

Old records reveal that Simpson’s sugar plantations at the Tilston and Bounty Hall estates on Jamaica owned hundreds of slaves. Pages of ‘Returns’ for 1820 lists all the male and female slaves in the owner’s possession, giving their name, colour, age (if known), heritage (African or Creole) and ‘remarks’ (usually recording the mother’s name). Between 1817 and 1820 there had been 24 deaths, 12 births and two runaways, but soon, all but a handful of Simpson’s 280 slaves had been passed into the ownership of his creditors.

Abolition took time, for a whole trade structure had to be dismantled and vested interests had to be placated. The Act of 1807 only prohibited the carriage of slaves in ships – it was another 30 years before slavery in the British colonies was outlawed outright.

Key Whitehaven players in the Africa trade (which lasted from 1710-1769 and involved 69 slave voyages) were the Lutwidges, Hows, Flemings, and the Speddings. The Rum Story outlines the links of the Jeffersons wine merchants to sugar plantations in Antigua.

In the 1770s Whitehaven became home to freed slaves when Cumbrian families in Virginia returned home with their servants as the tobacco trade faltered. The first black policeman in Britain, who served at Maryport and Carlisle in the 19th century, was the son of a slave who disembarked at Whitehaven harbour.

Milham Hartley was principally a banker and industrialist in Whitehaven. He had inherited a share in Hartley’s Bank (in Coates Lane) which was founded by his father John in 1786 before establishing the Joint Stock Bank of Whitehaven in 1818 (now NatWest/RBS). Milham’s Christian name was taken from his mother Elizabeth’s maiden name. The family were also merchants (rope makers at Corkickle/Coach Road) and ship-owners, with involvement in the slave trade dating back to the 1760s. Milham and his brother Thomas carried on the family businesses.

Milham Hartley married Mary Lewthwaite of Millom, lived at Rosehill and served as High Sheriff of Cumberland in 1818. His brother Thomas lived at Gillfoot, Egremont.

The former Whitehaven YMCA at 44-45 Irish Street was built in the early part of the 18th Century by James Milham, a rich merchant and master of ships who wrote a book about navigating American waters. His fine house had two projecting wings, one his office and the other his warehouse. In 1706 he married Elizabeth of the well-known Gale family and the property at Irish Street remained in the family until it was sold in 1872 to a local chemist, William Kitchen. Kitchen lived there with wife Elizabeth, a housemaid and cook, until he abandoned town living for the countryside, and moved to Ellerslie, at Gosforth.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here