Have you got an air raid shelter hidden in your garden, or any wartime photos in an old drawer? Then York Civic Trust needs YOU. STEPHEN LEWIS reports

DO you think you might have an old air raid shelter hidden away at the bottom of your garden? Have you dug up what might be a bit of shrapnel - or does your house still bear the signs of having been repaired after being hit by a bomb?

Then the York Civic Trust wants to hear from you.

It is amazing just how many physical reminders of the Second World War air raids there still are in York, says Trust volunteer project manager Nick Beilby.

There is, for example, an air raid shelter in the grounds of the former Queen Anne's School (now St Olave's) in York.

Nick's sister went to Queen Anne's in the 1950s and 1960s, and knew all about it. "They called it the zoo, and it was where they kept animals," Nick says.

Hidden away on green land near the banks of the River Ouse at Clifton, meanwhile, is a more sinister survival of the air raids: a bomb crater.

When there's been a lot of rain, or the water level is high, it looks like an unkempt pond. But this is where one of the bombs dropped on the night of the Baedeker Raid in 1942 fell, says Nick.

Then there's the stuff that is entirely unrecorded.

"We get people saying things like: 'I think I might have an Anderson shelter in my back garden'," says Dr Duncan Marks, the Civic Trust's heritage planning officer. "And there are also people who think they might have something, but don't know what or how interesting it might be."

On the eve of the 77th anniversary (on Monday) of the great 1942 Baedaker air raid on York, the Trust has decided it is time to try to collate all this information.

Working with other heritage organisations including Explore York, Historic England, the city council, the University of York and the Yorkshire Architectural and York Archaeological Society (YAYAS), it is setting out to compline a complete database of information, records, photos and other material so as to better understand the impact that the air raids of the Second World War had on York.

The 'Raids Over York' project has already made a good start. The Trust and its partner organisations have managed to find a 1942 British Railways map which details exactly where every bomb dropped during the night of the 1942 Baedeker Raid fell.

They mainly hit around the Leeman Road area and what is now York Central, says Nick Beilby - demonstrating that the Germans knew exactly what they were doing, by targeting the city's rail manufacturing heartland.

A comprehensive list has also been compiled of York Civil Defence papers and documents that survive from the war. These include everything from handbooks detailing arrangements for the 'preservation of life, the relief of suffering, and the care of the homeless' in the event of an air attack, to casualty lists and records of bomb damage.

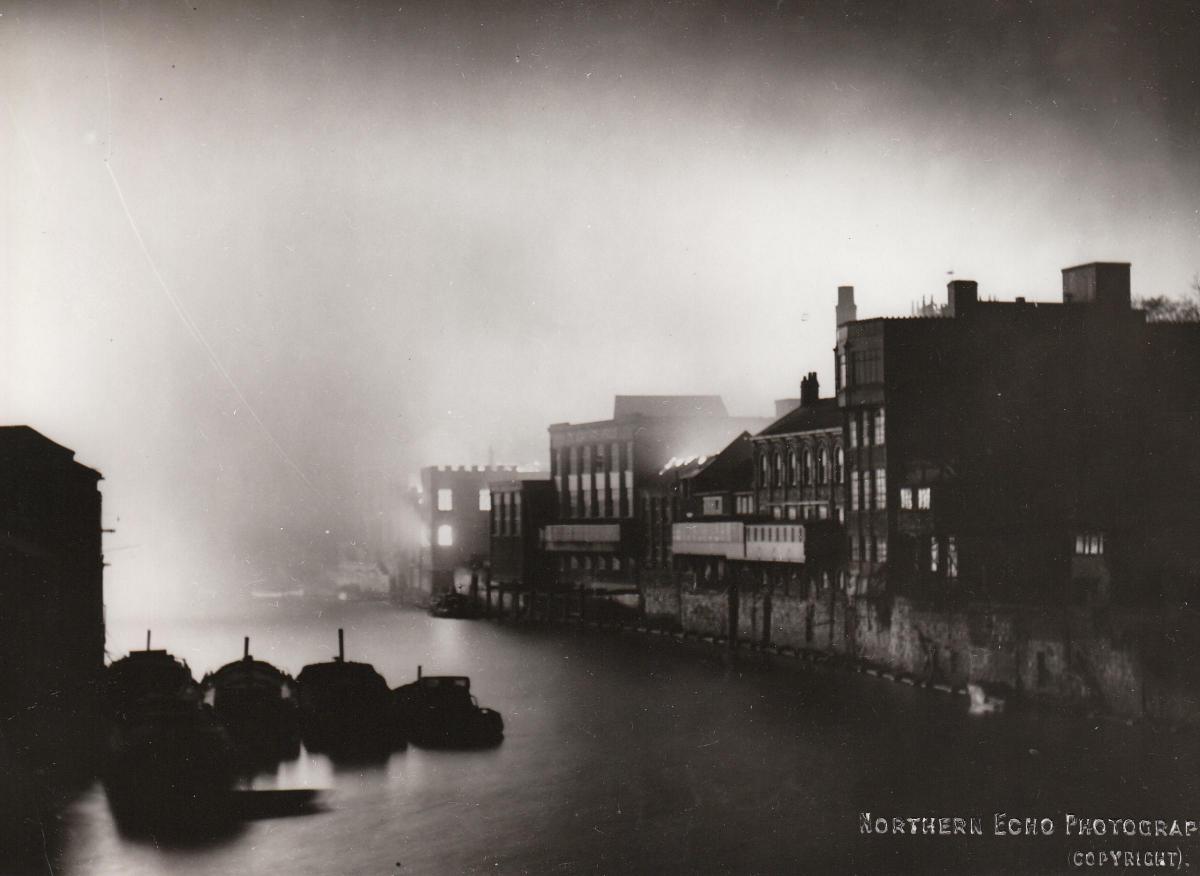

Queen Anne's Road after being bombed

But the Raids Over York project hopes to go much further. It wants people to come forward with information about any old air raid shelters they might have hidden away in their gardens, or with details of houses that were damaged in the war or local spots rumoured to be bomb craters, so as to put together as complete a record as possible of all the physical remains relating to the Second World War.

It also wants to collect historic photos, reports and maps - and stories.

"We want people's memories," says Duncan. "We want to collect first-hand accounts of those who might just remember from their childhood where bomb shelters were, where the bombs fell, and any other memories of the war in York that they have.

"Relatives and descendants of those who lived in York during the war will also likely have good second-hand knowledge of such memories, including where standing structures might still be."

Depending on the response, the hope is that by the 80th anniversary of the Baedeker Raid, in April 2022, we'll have a much better understanding of just how York coped with the air raids all those years ago.

And there's more. "We're hoping that we might be able to put up plaques, and create walking trails taking in structures like air raid shelters, buildings that were damaged, and bomb craters," Duncan says. There could also be an exhibition at Explore York, a dedicated website where members of the public can find out about the air raids - and even a digital interactive map, built by 'layering' maps from different years throughout the period of the war one on top of the other.

It all depends on members of the public coming forward with that information, those memories, and those old photos, however.

Over to you...

- If you have information about wartime structures such as air raid shelters or bomb craters in York, or if you have old photos, remember the war itself, or have stories that your parents or older relatives told you, the Civic Trust would like to hear from you. Email RaidsOverYork@outlook.com, call 01904 655543, or write to Dr Duncan Marks, York Civic Trust, Fairfax House, Castlegate YO1 9RN

York's surviving bomb crater

The bomb crater at Clifton

One wartime survival in York that is known about is the bomb crater near the river at Clifton.

It's in the green area between St Peter's School and the River Ouse. When the weather is wet the crater often fills with water. But it is a genuine legacy of the great Baedeker Raid of April 29, 1942, says Civic Trust volunteer project manager Nick Beilby.

The crater was brought to Nick's attention by his friend Donald Horsfield, who lives nearby.

"And it was made during the bombing raid of April 29, 1942," Nick says. "German bombers hit the engine sheds in Leeman Road, then hit the river bank here, then later hit Westminster Road, destroying houses there and killing some people."

Westminster Road in the aftermath of the Baedeker Raid

As part of the Raids Over York project, the Civic Trust plans to preserve the crater.

"There was a concern that it could be filled in because nobody knew what it was," Nick says.

"So we have fenced it off, and we plan to put interpretation boards around it to explain its history."

The York air raids

There is a misconception that there was only one wartime air raid on York, says Nick Beilby - that of April 29, 1942, which has gone down in history as the Baedeker Raid.

That was certainly by far the worst air raid on York. Casualty figures vary, but it certainly left more than 100 people dead, many of them York civilians, and destroyed or damaged many buildings, including engine sheds at York Railway Station, the Guildhall, St Martin's Church in Coney Street and the Bar Convent. Queen Anne's School, Poppleton Road School and the Manor Higher Grade School were also damaged.

There were several other air raids on York, however, some of which resulted in significant damage and loss of life.

They included

- August 11, 1940: Bombs fall on York Cemetery and Cemetery Road, damaging 69 houses and seriously injuring two people

- October 29, 1940: Sefton Avenue and Elmfield Avenue hit, two people killed

- August 8, 1942: Skeldergate and Walmgate hit. One person killed, 9 seriously injured, 400 properties damaged

- September 24, 1942: Hungate, Walmgate and Tang Hall hit. Two people killed, three seriously injured

- December 17, 1942: The York Gas Works and Park Grove hit. Two people killed, nine seriously injured. Damage to the gas works and to Park Grove School

The eyewitness

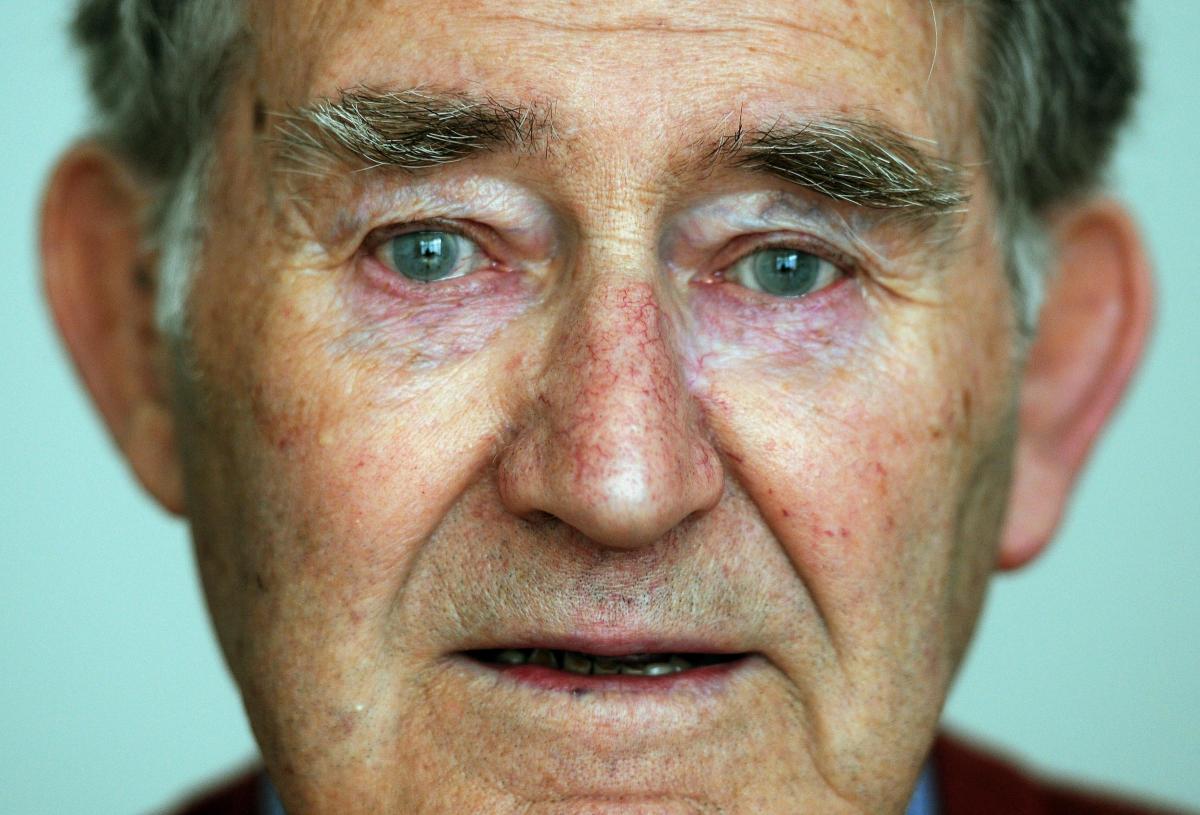

David Wilson in 2012

David Wilson and his family lived at the Guildhall, where his father Jock was the caretaker, during the war. They were there the night the bombs fell – and survived.

David, who was 11 at the time, told his story to The Press in 2012.

The family lived in the caretaker’s flat, on the second floor above the Victorian municipal offices next to the medieval Guildhall.

David remembered the Observer Corps’ warning bell going off, followed by the sirens. With that, all hell broke loose.

The bombs raining down on the Guildhall were only incendiaries – but explosive bombs fell on Blake Street, not far away.

David, his mum and older sister Margaret, who was in the ATS, went down to the supposedly bomb-proof ARP headquarters in the basement. But his dad was on fire watch – and stayed above, vainly trying to tackle the flames.

“He couldn’t deal with all the incendiaries,” David recalled. The roof of the Guildhall had been undergoing repairs. There was a floor of new timber just beneath the roof so that workmen could reach it, plus scaffolding and shavings.

“The whole thing was a tinderbox,” David recalled. “It caught fire and just went up.”

David’s own most vivid memory was of going out onto the balcony overlooking the river behind the Guildhall. It seemed the whole riverfront was on fire: the Guildhall, and buildings on the opposite side of the river too.

It was frightening, he admitted – but a sight he wouldn’t have missed. “You’d never, ever see that again.”

Eventually, as the fires at the Guildhall burned more fiercely, the family was evacuated to the Mansion House.

Margaret was in her ATS uniform, and wearing a tin hat. It was fortunate that she was. As they walked along the passage beside the Guildhall, lead dripped off the roof and on to his sister’s head.

“If she hadn’t had that helmet on...”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel